- Received March 28, 2022

- Accepted April 22, 2022

- Publication June 10, 2022

- Visibility 2 Views

- Downloads 0 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijn.2022.024

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Comparison of effect of rhythmic auditory cueing versus rhythmic visual cueing on gait abnormalities with gait parameters in Parkinson’s patients

- Author Details:

-

Krutika Naik *

-

Sayli Paldhikar

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common, degenerative disorder in the geriatric age group which causes severe neurological consequences on the population affected by the disease.[1] There has been a rise in the elderly Indian population from 5.6% in 1961 to 7.1% in 2001 and 8.6% in 2011. About 5-60% of total neurological disorders amount to Parkinson’s patients, with slight changes in the geographical areas.[2] The work of the basal ganglia is mostly to plan and program the movement by deciding and lowering specific motor synergies. Parkinson’s disease is associated with a deficiency of dopamine which occurs due to degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons. There are other deficiencies in neurotransmitters as well (e.g. serotonin, norepinephrine). [3], [4]

The process of development of Parkinson’s disease consists of a reduction in the Dopaminergic stores of substantia nigra with its consequent depigmentation and the presence of Lewy bodies. The loss of dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra leads to changes in both pathways of the basal ganglia, causing a reduction in excitatory thalamic input to the cortex and perhaps a reduction in negative inputs that leads to the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.[5], [6] The highlighting features in the majority of Parkinson’s individuals are bradykinesia, hypokinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability. Due to the several other effects along with basal ganglia degeneration the gait and balance are also impaired. These malfunctions occur because of severe loss of dopaminergic innervation of the basal ganglia. Parkinson’s patients commonly suffer from gait disturbances and this leads to the underlying disability and impairment.[7], [8]

Parkinson’s patients generally show signs of spatial and temporal dysfunction. There is an adverse effect on stride length and cadence of the PD patients.[9], [10] The patients present with an abnormal stooped posture further causing a festinating gait and a reduced stride. The patient takes multiple short steps to catch up with his center of mass to avoid falling.[3] Gait hypokinesia is the first to appear and is responsible for the decrease in velocity.[11] The gait profile of PD patients is such that they show a shuffling pattern indicating a reduced stride length along with a decreased cadence.[9] The patients also show inconsistency in steady gait rhythms. These gait abnormalities further have adverse effects on the patient's gait parameters, further adversely altering their gait.

The majority of the patients who have such gait abnormalities show better results from the effect of external cues and attentional strategies.[3], [12], [13] Rhythmic sensory cues have been known to affect walking dynamics and hence are known to be of great importance in the neurological rehabilitation of patients.[9], [14] Rhythmic visual cueing is the neurological technique used to facilitate rehabilitation by providing visual stimulation which intrinsically improves the gait by altering the gait parameters.[15] Researches have shown that auditory stimuli are shown to be more effective than no stimuli at all. Constant Rhythmic sound appropriately overstimulates the spinal motor neurons, this causes a reduction in the reaction time for the given motor command.[9]

However, there aren’t any researches that compare the effectiveness of rhythmic auditory and rhythmic visual cueing to improve the patient's gait. Hence this study will be performed to find the effectiveness of rhythmic auditory and visual cueing over each other on the gait parameters of PD patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A Randomised Case-Control study design with a correlational technique wherein the evaluation of the relationship of the variables between two different groups was performed (baseline & post-intervention). For gait analysis, the primary variables were step width and cadence while for the 10m walk test the average velocity was considered for both groups.

Participants

The participants were 14 Parkinson’s patients within the age group of 40 to 80. There was a randomisation of participants in both groups according to chit method. They were recruited from a Parkinson’s society in Pune, India. Before the interventions were begun, the participants were given an information sheet that explained the contents and procedure of the study and an informed consent was taken. The inclusion criteria were that the participants were on Modified Hoen and Yahr stage of 2.5 to 4, were able to walk 10m without assistance, had corrected vision and hearing aid and their MMSE score were between 20 to 24 and above mild dementia along with the POMA Score of 19 to 24 (medium risk of fall). The exclusion criteria were participants with high-risk falls, vestibular problems, fractures of the lower limbs in the past 6 months, loss of kinaesthesia and proprioception, could not follow commands. Out of the group final 14 participants who fit the selection criteria were included in the intervention. They were divided into two groups by the Sampling technique of Random allocation by Chit Method. Written consent was taken from all the participants according to the Helsinki declaration. The study was performed as a pilot with a sample size of 14 subjects. The study setting was Pune, India. The subjects were located in Pune and were grouped by the Sampling technique (Random allocation by Chit Method). The duration of the study was 4 weeks with the subject participating in it 3 times per week. The materials required were the metronome, chart paper, ink bottle, chair, measuring tape, colorful stripes. A Case-Control study design was performed with a correlational technique wherein the evaluation of the relationship of the variables with two different groups was performed

Procedures

The number of participants to be included also depended on the sample size which was calculated manually with the assistance of a statistician. The approval was first taken from the Institutional Ethical Committee members before starting the intervention. Participants submitted a signed consent form. The participants were divided into two Experimental groups i.e Experimental group A and Experimental group B. Participants in Experimental group A were given 4 weeks of Rhythmic Auditory Cueing along with conventional treatment for gait. Participants in Experimental group B were given 4 weeks of Rhythmic Visual Cueing along with conventional treatment for gait. The gait parameters and 10 m walk test scores of all the participants were calculated before the intervention began.

Rhythmic auditory cueing

The Patient is supposed to walk on a 10m pathway for 30 minutes while following the auditory cues by using the technique of metronomic beats. The protocol was divided into 3 parts.1) Walking on a flat surface for 10 min, 2) Stair stepping for 10mins ([Figure 1]), 3) Stop and go for 10mins. The duration of this intervention was 4 weeks (3 days each week). The Metronomic beats were equal to the pre-test cadence in the first week, 5 to 10% faster each week for 4 weeks 3 times per week.

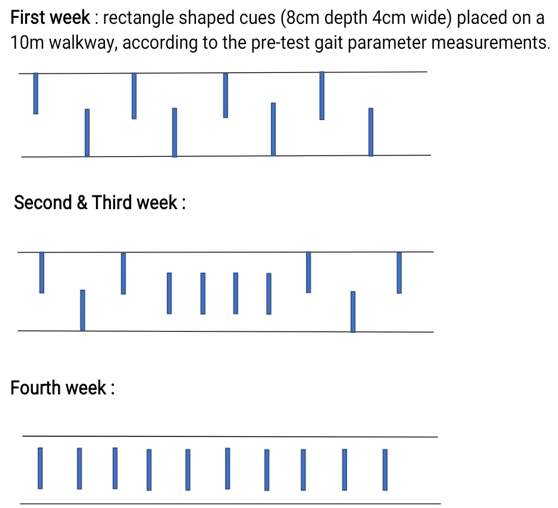

Rhythmic visual cueing

The Patient is supposed to walk on a 10m pathway by following the visual cues that are present as colorful stripes on the ground for 30 minutes as shown in [Figure 3] and [Figure 4]. The feet placement while walking on the pathway should be on the rectangular stripes. The placement was changed each week as shown in [Figure 1]. The duration was 4 weeks (3 days/week).

Outcome measures

The Crude method of gait analysis

The analysis of the patient’s gait parameters is performed using the crude method. In this method, the patient is first told to dip his feet in the ink and then walk on the chart paper roll of 5 meters.[16] The patient’s gait parameters are measured by using measuring tape by the experimenter.

10m Walk test

A 10m walk test is used to calculate the walking velocity of the person.[17] The participant is told to walk 10m at his normal speed and the time taken is noted 3 times. After that, the patient walks for 10m as fast as possible and 3 values are noted in seconds.[18] The average values for slow and fast speeds are taken and their respective values calculated. The normal values for the age group 40-49 is 1.43/1.39; age 50-59 1.43/1.31; age group 60-69 1.34/1.24; age group 70-79 is 1.26/1.13. [19]

Statistical analysis

The analysis of the data was performed using SPSS (version 25.0 IBM Corp., USA). The homogeneity test was performed using the chi-squared test for categorical values. For normality test, the Kolmogorov- Smirnov test was used. The Mann-Whitney test was used to verify the effect of the difference between the two groups while the one-tailed Wilcoxon’s test was used to determine differences before versus after the interventions. The calculation of Cohen’s d was performed to determine the effect size of the treatment. All Statistical Significance levels were at (0.05).

Result

The research was performed from September 2019 to March 2020. There was recruitment of 14 participants with no dropouts. The general characteristics of the group are as described in [Table 1]. There was a significant improvement in the post intervention scores of stride length step width, cadence when compared to their pre intervention scores in both groups. There was a statistically significant improvement in both the groups in their before versus after intervention scores with (p<0.05).When an analysis was performed to compare the effectiveness of both the groups, there was significant improvement in the step width and cadence and 10m walk test scores of group A. The comparison of post-intervention scores between the two groups showed better results in groups A with (p<0.05). The calculation of Cohen’s d showed statistically significant values as showed in [Table 2].

|

General characteristics |

Experimental Group A (n=7) |

Experimental Group B (n=7) |

X 2 /t |

|

Age (years) |

70/4 |

64/8 |

0.536 |

|

Sex (female/male) |

2/5 |

2/5 |

-0.23 |

|

Height (cm) |

165/8 |

164/7 |

-0.342 |

|

Weight (kg) |

65/ 8 |

66/7 |

-0.821 |

|

|

|

Group A |

Group B |

Cohen’sd |

P value |

||

|

|

|

Mean (SD) |

Median |

Mean (SD) |

Median |

|

|

|

Stride |

Pre |

61.4(19) |

61 |

68(19.3) |

55 |

0.1101 |

P<0.05 |

|

Length |

Post |

76.4(16.7) |

70 |

6.14(4.9) |

59 |

||

|

Step width |

Pre |

12.6(2.06) |

10 |

11(3.36) |

10 |

2.271 |

P<0.05 |

|

|

Post |

7.7(0.7) |

18 |

1.8(1.14) |

12 |

||

|

Cadence |

Pre |

90(6.9) |

87 |

92.4(14.2) |

86 |

0.226 |

P<0.05 |

|

|

Post |

12.7(3.2) |

99 |

7.71(10.3) |

90 |

||

|

10m walk test |

Pre |

0.9(0.12) |

0.7 |

0.7(0.3) |

0.6 |

0.800 |

P<0.05 |

|

|

Post |

0.13(0.06) |

0.8 |

0.39(0.1) |

0.9 |

Discussion

The Aim to perform this study was to Compare the Effect of Rhythmic Auditory versus Rhythmic visual cueing in gait parameters of Parkinson’s patients. The Participants in this study were within the age range of 40-80 years. They were from both genders. The participants had a Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale of 2.5 to 4 and a POMA score of 19 to 24.

There has been a successful use of multisensory cueing for Parkinson’s patients. The patients in both the groups showed an affinity towards cueing due to which the result indicates that there was an improvement in the gait parameters as well as the 10m walking test scores post-intervention. This supports the findings of previous researches which has stated that Sensory cueing has a strong effect on improving Parkinson’s gait.[20] Cueing is known to particularly be more impactful if given for a longer period.[21]

When comparison of post-intervention results of both the groups was performed the patients in group A showed an increased step width, improvement in their cadence values and a better 10m walk test scores indicating that (p-value < 0.05) This finding can be supported by various researches that state, Rhythmic movement prefers Auditory Rhythms more as compared to Visual Rhythms.[22], [23] There are several types of auditory cues beneficial for Parkinson’s patients that help in improving the patient’s gait deficits.[24] The auditory cues given at a different frequency of beats caused significant improvement in the walking parameters of the patients.

There are several types of auditory cues beneficial for Parkinson’s patients that help in improving the patient’s gait deficits.[24] The auditory cues given at different frequencies of beats caused significant improvement in the walking parameters of the patients.

The patients in group B showed a non-significant result as compared to the values of their cadence. This is in line with the findings that state that visual cues cause non-favorable effects on the cadence of the patients.[25] Some of the research also states that patients with freezing have better effects as compared to non-freezers.[26] Auditory and visual cues when given to the patients in combination did not have better results as compared to auditory and visual cues alone.[27] Rhythmic cues help in improving turning performance in patients with both freezing & non-freezing.[28]

The research results showed that there was a significant improvement in both groups respectively in their gait parameters. However when both the groups were compared for their improvements, Rhythmic auditory cueing showed better results. [22], [25]

While performing the research, patients in the Rhythmic auditory cueing group showed more enthusiasm to perform the activity as compared to the Rhythmic visual cueing group. There was a significant improvement in gait performance in PD patients.[29] Auditory cueing had a favorable effect on the cadence on the other hand visual cueing benefitted the stride length.[30], [29], [31] The use of these cues on the patient at the same time did not affect gait more than each cue individually.[27]

Use of visual cues on the gait of freely walking Parkinson’s patients improved their stride length without any changes in their walking speed.[30], [31] Metronome therapy had positive effects on their gait by showing favorable results in the gait quality and reduced freezing episodes.[29] There have also been researches quantifying the long-term effects of a short-term intervention that uses external cues given by a sensor. [32]

This study was performed on a small sample size which might be a limitation in its effectiveness. The duration of the research is 4 weeks which is a long time and as there is less motivation in Parkinson’s patients this might lead to decreased patient compliance. In further research of this topic, there is a need to select a more diverse group and more participants need to be recruited. Also, the assessment of cortical activity during brain imaging studies at baseline, during & post-intervention can add interesting results to the study.

Conclusion

The clinical study takes us to the conclusion that the intervention of Rhythmic auditory cueing proves to be more effective in improving the patient’s stride length, cadence, and step-width thus helping in improving the patient's walking pattern.

Acknowledgement

The author recognises the contribution of the participants in this group and acknowledges the support provided by the supervisor and the statistician.

Conflict of I nterest

The researcher claims no conflict of interest.

Source of Funding

None.

References

- K J Miller, D Suárez-Iglesias, M Seijo-Martínez, C Ayán. Physiotherapy for freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Neurol 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UB Muthane, M Ragothaman, G Gururaj. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease and movement disorders in India: problems and possibilities. JAPI 2017. [Google Scholar]

- SB O’sullivan, TJ Schmitz. Physical rehabilitation. 5th Edn.. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- R Balestrino, AHV Schapira. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D Umphred, RT Lazaro. Neurological Rehabilitation Sixth Edn.. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- A Samii, J G Nutt, B R Ransom. . Parkinson's disease. Lancet 2004. [Google Scholar]

- M Jeffrey. Hausdorffa Gait dynamics in Parkinson’s disease: Common and distinct behaviour among stride length, gait variability, and fractal-like scaling. Chaos 2009. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- M Hallett. Parkinson's disease tremor: pathophysiology. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012. [Google Scholar]

- E Sejdić, Y Fu, A Pak, JA Fairley, T Chau. The effects of rhythmic sensory cues on the temporal dynamics of human gait. PLoS One 2012. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- M Pistacchi, M Gioulis, F Sanson, E De Giovannini, G Filippi, F Rossetto. Gait analysis and clinical correlations in early Parkinson's disease. Funct Neurol 2017. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- MH Thaut, GC Mcintosh, RR Rice, RA Miller, J Rathbun, JM Brault. Rhythmic auditory stimulation in gait training for Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 1996. [Google Scholar]

- PA Rocha, GM Porfírio, HB Ferraz, VF Trevisani. Effects of external cues on gait parameters of Parkinson's disease patients: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- C Cassimatis, K P Liu, P Fahey, M Bissett. The effectiveness of external sensory cues in improving functional performance in individuals with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Rehabil Res 2016. [Google Scholar]

- G Frazzitta, R Maestri, D Uccellini, G Bertotti, P Abelli. Rehabilitation treatment of gait in patients with Parkinson's disease with freezing: a comparison between two physical therapy protocols using visual and auditory cues with or without treadmill training. Mov Disord 2009. [Google Scholar]

- L Rochester, V Hetherington, D Jones, A Nieuwboer, A M Willems, G Kwakkel. The effect of external rhythmic cues (auditory and visual) on walking during a functional task in homes of people with Parkinson's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- DD Boenig. Evaluation of a clinical method of gait analysis. Phys Ther 1977. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- B Lindholm, MH Nilsson, O Hansson, P Hagell. The clinical significance of 10-m walk test standardizations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 2018. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- MJ Watson. Refining the ten-metre walking test for use with neurologically impaired people. Physiotherapy 2002. [Google Scholar]

- RW Bohannon, AW Andrews, MW Thomas. Walking speed: reference values and correlates for older adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1996. [Google Scholar]

- TC Rubinstein, N Giladi, JM Hausdorff. The power of cueing to circumvent dopamine deficits: a review of physical therapy treatment of gait disturbances in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2002. [Google Scholar]

- A Nieuwboer. Cueing for freezing of gait in patients with Parkinson's disease: a rehabilitation perspective. Mov Disord 2008. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- BH Repp, A Penel. Rhythmic movement is attracted more strongly to auditory than to visual rhythms. Psychol Res 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MKY Mak, ISK Wong-Yu. Exercise for Parkinson's disease. Int Rev Neurobiol 2019. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- A Ashoori, D M Eagleman, J Jankovic. Effects of Auditory Rhythm and Music on Gait Disturbances in Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol 2015. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- P Arias, J Cudeiro. Effects of rhythmic sensory stimulation (auditory, visual) on gait in Parkinson's disease patients. Exp Brain Res 2008. [Google Scholar]

- HY Chang, YY Lee, RM Wu, YR Yang, JJ Luh. Effects of rhythmic auditory cueing on stepping in place in patients with Parkinson's disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- S Wattananon, GS Morris, BR Etnyre, J Jankovic, EJ Protas. Effects of visual and auditory cues on gait in individuals with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci 2004. [Google Scholar]

- A Nieuwboer, K Baker, AM Willems, D Jones, J Spildooren, I Lim. The short-term effects of different cueing modalities on turn speed in people with Parkinson's disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009. [Google Scholar]

- W Enzensberger, U Oberländer, K Stecker. Metronome therapy in patients with Parkinson disease. Der Nervenarzt 1997. [Google Scholar]

- S Bagley, B Kelly, N Tunnicliffe, G ITurnbull, JM Walker. The effect of visual cues on the gait of independently mobile Parkinson's disease patients. Physiotherapy 1991. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- RDM Roiz, EWA Cacho, A Cliquet Jr, EMAB Quagliato. Analysis of parallel and transverse visual cues on the gait of individuals with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Int J Rehabil Res 2011. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- LP Carvalho, KKV Mate, E Cinar, A Abou-Sharkh, AL Lafontaine, NE Mayo. A new approach toward gait training in patients with Parkinson's Disease. Gait Posture 2020. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]